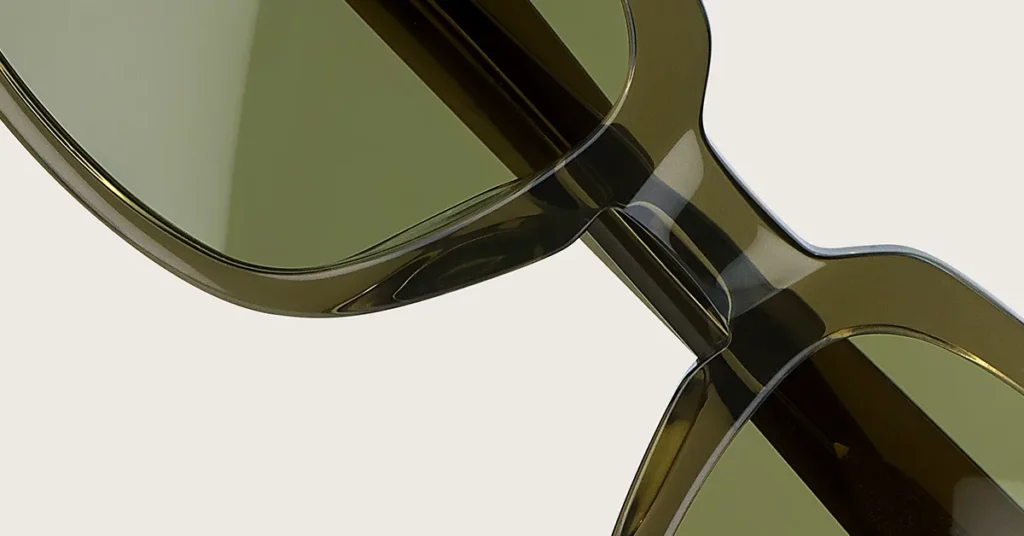

You’ve designed the perfect frame and built a compelling brand story. Yet, one acronym often stands between your vision and a warehouse full of product: MOQ. For new founders, this number can feel like an insurmountable barrier, sparking fears of wasted capital and unprofitable inventory. But what if you could reframe it? This guide moves beyond simple definitions to give you a proprietary framework, turning MOQ from a hurdle into your first great strategic decision.

Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) is the fewest units a manufacturer requires for a production run, typically 200-300 units per model for custom acetate eyewear. This threshold ensures the factory covers fixed costs like machine setup and raw materials, making the production financially viable. It’s a standard metric across the entire manufacturing industry.

MOQ 101: What Founders Must Know About Manufacturing’s Core Metric

What is a Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ)?

Definition: The Minimum Order Quantity (MOQ) is the fewest units a supplier is willing to sell in a single transaction. It can be a set number of units (e.g., 300 frames) or a minimum order value (e.g., $10,000).

Simple Analogy: Think of an MOQ as the “cover charge” for using a factory’s production line. A venue has fixed costs to open for the night—staff, electricity, security—and must sell enough tickets to cover those costs. A factory has similar upfront costs for machine setup and labor, and the MOQ ensures the production run is profitable.

The primary purpose is to achieve economies of scale, an economic principle where the cost per unit decreases as production volume increases. This allows the factory to spread its fixed costs over more units, lowering your price. It’s also important to understand the difference between a simple MOQ (e.g., 300 total units of one style) and a complex MOQ (e.g., 300 total units, with a minimum of 100 per colorway), which is common in eyewear.

Why Eyewear Manufacturers Must Set MOQs

Manufacturers don’t set MOQs to be difficult; these numbers are a direct reflection of their cost structure. A major factor is the high cost of machine setup. Calibrating multi-axis CNC machines or preparing precision steel molds for injection molding incurs significant costs that must be spread across the total number of units in an order. For small orders, this per-unit setup cost becomes impossibly high.

Another critical factor is the supply chain domino effect. Eyewear manufacturers are subject to the MOQs of their own raw material suppliers. If a premium acetate supplier like Mazzucchelli requires a 250 kg minimum order for a custom color, the frame factory must purchase that entire quantity. This raw material constraint is then passed down to your brand as a higher MOQ for the finished frames.

Finally, MOQs are essential for managing labor costs and production line efficiency. Processing many small, disparate orders is administratively inefficient and disrupts workflow. Setting minimum quantities allows for better production scheduling and more effective use of machinery and skilled technicians, which reduces costly downtime. Ultimately, MOQs are a necessary financial tool for a factory’s long-term viability.

What Really Drives MOQ Numbers in the Eyewear Industry?

Factor 1: The Impact of Materials (Standard vs. Custom Acetate)

The material you choose is one of the biggest levers on your MOQ. Opting for a standard, in-stock material like black or tortoise acetate almost always results in a lower MOQ. Manufacturers buy these common colors in bulk, so they have inventory ready. This means they can offer it to you for a smaller production run without placing a new order with their own suppliers.

Pro Tip: For a new brand, choosing from a factory’s existing library of “in-stock” materials is one of the most effective strategies to secure a lower MOQ and launch your first collection with less upfront capital.

Conversely, a custom-developed Mazzucchelli acetate pattern will lead to a very high MOQ. This is because the MOQ is dictated by the raw material supplier, not the frame factory. A world-class supplier produces acetate to order and may have a minimum of 250 kg for a specific custom color. The frame factory must purchase this entire batch, which translates into a much larger order requirement for your brand, often thousands of units.

Factor 2: The Impact of Manufacturing Process (CNC vs. Injection Molding)

Your chosen manufacturing process fundamentally alters the MOQ conversation by changing the upfront investment required. CNC machining, which carves frames from acetate blocks, has lower setup costs because it doesn’t require a unique mold. This makes it the ideal process for new brands needing lower quantities, even though the per-unit cost is higher. In contrast, injection molding requires a massive upfront investment in a custom steel mold, which must be amortized over thousands of units.

| Feature | CNC Machining (Acetate) | Injection Molding (TR90, etc.) |

| Typical MOQ | Lower (200-500 units) | Very High (5,000+ units) |

| Tooling Cost | Low (No custom mold) | Extremely High (Precision steel mold) |

| Unit Cost | Higher at volume | Very low at volume |

| Best For | Startups, premium/niche collections | Mass-market, high-volume products |

Pro Tip: For your first collection, focus on CNC-machined acetate. It provides the flexibility to test the market with a reasonable MOQ before committing the capital required for high-volume injection molding.

Factor 3: The Impact of Design Complexity

As a rule, the more complex your design, the higher the MOQ. A frame with intricate milling, custom hardware, or multiple unique components requires more specialized tooling and labor. These factors increase the fixed costs of the production run, which in turn requires a higher MOQ for the factory to recoup its investment.

Most Importantly: Your final MOQ is often a “stack” of multiple MOQs from the entire supply chain. A factory might have a 300-unit MOQ for assembly, but if your design requires a custom-branded hinge from a specialty supplier with a 50,000-unit MOQ, that hinge becomes the real barrier. Your brand’s “True MOQ” is always dictated by the highest and least flexible MOQ of any single custom component in your design.

Best Practice: The most direct path to a lower MOQ is to reduce the number of custom components that trigger these sub-supplier minimums. In my two decades in this industry, I’ve seen that opting for a factory’s high-quality “stock” components—like standard hinges and wire cores—is the smartest move for new brands. This simplifies the negotiation to focus only on the frame assembly MOQ, which is often much more flexible.

The Kssmi Eyewear Founder’s MOQ Framework: A 3-Part Decision Model

Most founders approach their MOQ as a simple negotiation, trying to get the lowest number possible. This is a mistake. The MOQ isn’t just a number to be negotiated; it’s a strategic decision that requires a data-driven approach. We developed this framework to stop you from guessing and start making an informed choice based on three critical perspectives.

Simple Analogy: Think of this framework as building a three-legged stool for your business. A stool with only one or two legs—like focusing only on what you can afford—is unstable and will quickly collapse. You need the stability of all three legs—Financial, Market, and Strategic—to build a sustainable and successful brand from your very first production run.

Part 1: Calculate Your Financial MOQ (The Hard Ceiling of What You Can Afford)

This calculation determines the absolute maximum number of units your business can safely afford. It starts with understanding your true costs. To do this, you must accurately estimate your Landed Cost Per Unit, which is the all-inclusive cost to get a single frame from the factory floor to your warehouse door, ready for sale. It is far more than just the factory’s quoted unit price.

A complete Landed Cost calculation must include:

- Factory Unit Cost: The price per frame, often quoted as FOB (“Free on Board”).

- Per Unit Freight: The cost of shipping from the factory to you.

- Per Unit Customs/Duties: All tariffs and taxes levied by the importing country.

- Per Unit QA/Overhead: Fees for third-party inspections, brokerage, and payment processing.

Critical Warning: For U.S. brands importing from China, be aware that Section 301 tariffs have dramatically increased costs. As of mid-2025, the total combined tariff rate on plastic eyeglass frames from China can be approximately 155%. A frame with a $15 factory cost could incur over $23 in tariffs alone. Always verify current rates.

Once you have your estimated Landed Cost, apply the 70% rule to your available capital. Never allocate more than 70% of your startup capital to inventory; the remaining 30% is a non-negotiable buffer for marketing and unforeseen costs. The final calculation is: (Available Capital x 0.70) / (Estimated Landed Cost Per Unit) = Your Financial MOQ.

Part 2: Calculate Your Market MOQ (The Realistic Target of What You Should Order)

Since new brands lack historical sales data, you must use “Attribute-Based Forecasting”. This method uses market data and competitor analysis to create a reasonable, data-informed estimate of initial demand. It provides a target for what you should order, based on market signals, not just what you can afford.

Here’s how to execute this four-step process:

- Identify a close competitor’s product with similar attributes and a similar target audience.

- Estimate their monthly sales volume using a suite of market intelligence tools (e.g., Similarweb for web traffic, Earnest Analytics for consumer transaction data).

- Conservatively project capturing a small percentage (e.g., 15-20%) of their estimated volume. As a new entrant, you must be realistic about your initial market penetration.

- Multiply your projected monthly sales by your first sales cycle (e.g., 6 months). This gives you a data-informed target for your initial order quantity.

Part 3: Align with Your Strategic MOQ (The Smart Choice for Your Brand)

The final step is to align your order quantity with your long-term brand vision. The “right” MOQ isn’t just about financials or forecasts; it’s about what kind of brand you’re building. This decision matrix helps you choose a partner whose capabilities match your brand archetype.

| Brand Archetype | Priority | Ideal MOQ | Unit Cost | Strategic Outcome |

| The Trend-Setter | Flexibility & Speed | 150-300 units | Higher | Test more styles, react quickly to market trends, lower initial risk. |

| The Enduring Classic | Quality & Unit Economics | 500+ units | Lower | Build a brand on craftsmanship, achieve better margins, signal commitment. |

The Bottom Line: In my experience, a successful first production run happens at the intersection of these three calculations. Your final order quantity must be a number you can safely afford (Financial), can realistically sell (Market), and that supports your long-term vision (Strategic). A mismatch in any one of these is a recipe for failure.

Beyond the Number: How Your MOQ Choice Defines Your Brand Strategy

The Founder’s Dilemma: Balancing Unit Economics, Cash Flow, and Inventory Risk

For a new brand, you must solve for cash flow first and profit margin second. A high-margin product that sits in a warehouse because you ran out of money for marketing is a failure. The primary goal of your first inventory purchase is to validate the product-market fit while preserving enough capital to fund the marketing required to generate those initial sales.

This creates a clear trade-off. A low MOQ means a higher unit cost but frees up precious cash for critical launch activities like digital advertising. This approach correctly prioritizes customer acquisition and market feedback over immediate profitability. Committing too much capital to a high MOQ on an unproven product is a fatal error, as the money trapped in unsold inventory cannot be used to pivot, market, or weather unexpected challenges.

The Low-MOQ Red Flag: Interpreting MOQ as a Quality Signal

It’s tempting to seek out the absolute lowest MOQ possible, but an unusually low number can be a major red flag. An extremely low MOQ for a custom acetate design often indicates you are dealing with a trading company, not a true manufacturer. These middlemen often lack deep product expertise and simply resell products from various factories, giving you little control over the production process or quality.

Simple Analogy: Think of a manufacturer’s MOQ as a quality signal, like a restaurant with a line out the door. The line might be an inconvenience, but it signals that they have a mature process and a product people value. A completely empty restaurant might be faster, but you have to wonder why no one else is there. A reputable factory’s higher MOQ reflects their investment in machinery and skilled labor, which makes tiny custom runs unprofitable but ensures a quality result.

A suspiciously low MOQ often means the supplier is cutting corners on materials or skipping critical quality control steps like hand-polishing. In my experience, the initial savings from a “too good to be true” MOQ are almost always erased by the high costs of customer returns, brand reputation damage, and unsellable inventory.

From Theory to Practice: How to Negotiate MOQs Like a Pro

Standard and Advanced Negotiation Tactics

Once you’ve used the framework to determine your ideal MOQ, you can enter negotiations with a clear, data-backed position. Here are four professional tactics:

- Offer a higher price per unit. This is the most direct approach. By offering to pay a 5-15% premium, you compensate the factory for the inefficiency of a smaller run and frame the negotiation as a collaborative partnership.

- Inquire about using in-stock materials. Ask the manufacturer what high-quality materials they already have in their inventory. Using their stock eliminates the raw material MOQ from their sub-suppliers, which can significantly lower your final number.

- Offer to produce during their slow season. If your timeline is flexible, ask if they have a slow period. Placing your order then helps them keep their lines active, and they may offer a lower MOQ in return for the convenient timing.

- The Kssmi Pro Tactic: De-risk their raw material purchase. If a custom material is driving up the MOQ, offer to pay for the entire minimum order of that raw material upfront. This removes the financial risk for the factory. They can then produce your smaller initial order and hold the rest for your future production runs.

The Negotiation People Forget: Spare Parts and Warranty

Common Mistake: Most founders focus exclusively on the MOQ for complete frames. They forget to negotiate a post-sale service plan, which can create huge future costs. If a customer’s frame breaks under warranty, you might be forced to order a full MOQ of 300 temples just to service that one claim. This is financially unsustainable.

Best Practice: Your manufacturing agreement must contain a dedicated clause for spare parts. During your initial negotiation, contractually obligate the manufacturer to provide a small percentage (1-2% is standard) of the total production quantity as spare parts. This ensures you have an inventory of temples, hinges, and screws ready to service warranty claims without being subject to the standard MOQ.

Conclusion

Minimum Order Quantity is not just a production number; it’s the first critical strategic lever you will pull as an eyewear founder. By using the 3-Part Framework to analyze your Financial, Market, and Strategic needs, you can move from an emotional guess to a data-driven decision. Remember that a low MOQ isn’t always good, and a high MOQ isn’t always bad—the goal is to find a partner whose capabilities and terms align with your brand’s unique vision. When you’re ready to build that partnership, our team is here to help.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is a realistic MOQ for a new custom acetate eyewear brand?

The industry standard for a custom OEM order is typically between 200 and 300 units per model. This is almost always split across 2-3 colorways, meaning a 300-unit order would require at least 100 units per color.

2. Can I find a manufacturer with no MOQ?

Yes, but these suppliers are typically offering a private label service on their existing, in-stock frame designs, not true custom manufacturing. For a fully custom product, a “no MOQ” offer is a major red flag that may indicate a low-quality trading company.

3. How much more does a lower MOQ typically cost per unit?

While there is no universal rule, you should be prepared to offer a 5-15% premium on the per-unit price. This higher price fairly compensates the manufacturer for the loss of efficiency on a smaller production run where fixed costs are spread over fewer units.

4. Does my choice of lens color or type affect the MOQ?

Yes, it can. Specialized lenses are subject to their own MOQs from sub-suppliers. Creating a custom lens tint or using a specific polarized film is a batch process, and the lens supplier may have a minimum order that is higher than your frame MOQ.

5. When in the process should I start negotiating the MOQ?

The best time is right after you have received and approved the final pre-production samples. At this stage, both you and the supplier have invested time and resources, creating a collaborative environment where both parties are motivated to find a workable solution.